Target’s CIO has resigned following their massive credit card breach. This is pretty unsurprising. When I did security management I knew I’d be out the door if we had a credit card breach, and the worst-possible outcome of what I could have been associated with is dwarfed by Target’s incident.

What’s interesting to me, though, is all of the talk about responsibility, the value of PCI, and whose failing it was. There is no question that Target (and Neiman Marcus, and plenty of other merchants) failed at security when they lost control of sensitive data they were trusted and required to protect. I’ll get back to Target, because there were a lot of failures involved that went well beyond the merchants.

VeriFone failed when they released a vulnerable system. They provided the POS and card-swipe devices to Target, Neiman Marcus, and almost everywhere else on earth. The next time you pay for something in the US, look at the credit card terminal. It probably has a VeriFone logo on it, which means that merchant is likely as vulnerable as Target was.

VeriFone made a couple of critical mistakes. They failed to encrypt card info soon enough. The attackers’ software was able to grab card information from the terminal before it was encrypted. I’m not clear on whether that was still on the terminal itself (i.e. the swipe device) or on the cash register, but it doesn’t matter. It made it into memory in an application on some box where the attacker could see it and grab it. VeriFone also failed in permitting the attackers’ to get their software running on the device in the first place. It clearly wasn’t supposed to be there, and the system didn’t prevent its installation, and either didn’t detect it or didn’t think it was important. That’s a bigger failing than the encryption one.

PCI standards failed. I don’t know (and don’t care) whether Target was PCI compliant. The nature of the attack was more sophisticated than PCI was prepared to cope with. Let me say that again:

The nature of the attack was more sophisticated than PCI was prepared to cope with.

That’s pretty amazing, when you think about it. If you’ve never dealt with PCI (congrats, you were smarter than I was) it’s a beast of a standard. It is the most prescriptive, the most restrictive, the most rigorous, the most complicated, and the most fully audited security standard in the private sector. I know of many companies that stalled for years in even trying to achieve PCI compliance because it’s really hard, really expensive, and really unpleasant. Now that I no longer have to manage to it myself, I’m glad for all of those things. Credit card info is extremely valuable and it’s very disruptive to the lives of victims when thieves get their hands on it. Merchants don’t lose out, customers do, and a repressive security standard balances what is otherwise a very asymmetrical risk — it forces merchants to care.

And yet, with all of its dictates and difficulties, PCI failed. It didn’t address this incident.

I’m sure someone could find a requirement in PCI that could be interpreted in a way which applies. My best guess is it would be somewhere related to monitoring for unauthorized system changes. That’s probably syntactically correct, but it misses the bigger point. Nobody managed PCI that way. And that’s where you find the biggest failing.

Security management practices failed.

There are all sorts of ways to measure the success of a security management program. The most desirable and least useful is “did the bad guys get my stuff”. It’s least useful because it only tells you when you’re doing a bad job, never when you’re doing a good one, because you don’t know anything about the quality of the bad guys. So that’s not how people manage.

Instead, they tend to follow two basic measurements:

- Am I compliant with the necessary standards?

- Am I applying a reasonable and appropriate level of security?

There are countless KPIs, processes, goals, assessments, TPS reports, and dashboards used in actual practice, but every one of those matter-of-fact methods is a reflection of the two basic measurements.

We already know that the first wasn’t enough, since PCI failed. Neither was the second, not because Target wasn’t reasonable and appropriate in their security practices, but because nobody can realistically define what reasonable is.

The idea of reasonable security is both specific and nebulous, like obviousness in patents. If a skilled practitioner would find measures warranted in a given situation, reasonable security includes them. That can balance value, threats, risks, costs, and all of the other knobs you turn when making security decisions.

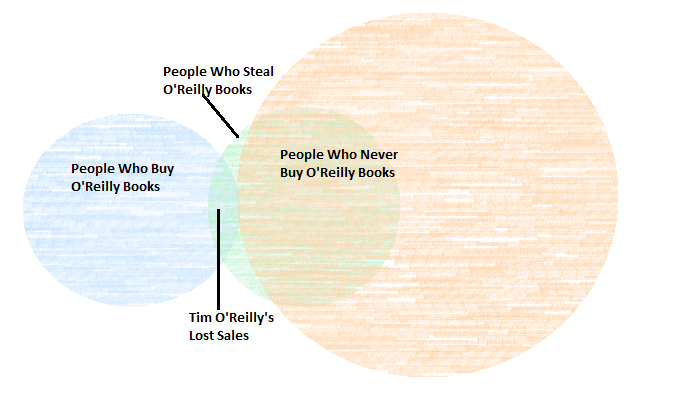

The pace at which threats are evolving is mind boggling. The value of an asset to an owner varies from the value of an asset to an attacker. The people doing the defending can’t see into the black markets and criminal underworld driving threats and shifting objectives, so they can’t get anything close to a fair assessment of the risk.

Further, they evaluate their risks, not systemic ones. Target lost a lot of credit card numbers, but they didn’t care at all about Neiman Marcus, or Michaels, or anyone else. VeriFone did, but VeriFone’s exposure in the attack was dramatically different than the merchants’.

Risk always looks simple. Likelihood of loss * Amount of loss = Risk. Target knew what the amount of loss would be, because the number of credit cards was countable. Likelihood of loss, though, encompasses more variables than any security manager can identify, much less account for. Value of the asset to an attacker, resources available to an attacker, applicability of an attack across ecosystems, aggregate value of assets within an ecosystem, hardware-level operations of commercial security devices, patience of an attacker, effectiveness of vendor security and trustworthiness of vendor code. You make a million assumptions in security management or you never make a decision.

And so, with all of that, I can come back to Target. VeriFone’s failings, PCI’s failings, the security community and the notion of reasonable action or best practice’s failings, the industry’s failing to clearly articulate the threat environment, and Target, who had to make decisions in all of this.

Did Target fail? Absolutely. They lost something like 110 million credit cards.

Did they fail doing everything right? I can’t say if they did, but they sure could have.

{ Comments on this entry are closed }